When the lion’s share of a playtext is speech – conversations between characters, or characters speaking alone – this means that speeches have a big job to do in representing the play’s plot, themes, moods, conflicts, actions and ideas. Despite an increasing tendency in more recent drama to include more action, the main focus of your average stage play is what people say to each other. Things are different in films and TV drama, where there is more space, more opportunities to use special effects and stunt performers, and where things can be edited after recording. In this section, we shall focus on pieces of drama where spoken words are more central than actions, in order to demonstrate how speeches expose both the concrete and the metaphysical in drama.

Our first example comes from William Shakespeare’s King Lear. In this play, the old king is about to divide his kingdom into three parts to give to his three daughters, and the decision to do so will lead to catastrophic – and ultimately tragic – consequences. But we, as first-time readers, know nothing about this when we begin to read the play, which starts out as a conversation between some supporting characters. Look at the left sidebar (bottom of the page for mobile devices) for a very simplified version of this speech.

KENT I thought the King had more affected the Duke of Albany than Cornwall.

GLOUCESTER It did always seem so to us: but now, in the division of the kingdom, it appears not which of the dukes he values most, for qualities are so weighed that curiosity in neither can make choice of either’s moiety.

KENT Is not this your son, my lord?

GLOUCESTER His breeding, sir, hath been at my charge. I have so often blushed to acknowledge him that now I am brazed to’t.

KENT I cannot conceive you.

GLOUCESTER Sir, this young fellow’s mother could, whereupon she grew round-wombed, and had, indeed, sir, a son for her cradle ere she had a husband for her bed. Do you smell a fault?

KENT I cannot wish the fault undone, the issue of it being so proper.

GLOUCESTER But I have a son, sir, by order of law, some year elder than this …

(1.1.1-18)

At this stage in the action, this conversation is more confusing than illuminating. The forthcoming division of the kingdom is alluded to in a somewhat indirect manner, but in fact, quite a lot can be learned from this exchange – while much of it will turn out to be less innocent than it seems.

Before we move on, it should be pointed out that the story of King Lear and the division of his kingdom was well-known to Shakespeare’s audience. It was an old legend, and had been performed on the London stage in a version by another playwright. The opening, therefore, plays with audience expectations. For us, however, things will take some untangling. In the old story, Lear is supposed to divide his kingdom equally between his three daughters, but decides to give only two of them a share because he is upset with the youngest daughter for not flattering him sufficiently.

First, let us look at this exchange on a somewhat superficial level. We understand that the speakers are noblemen, because they are called Kent and Gloucester, short for the Earl of Kent and the Earl of Gloucester. These titles were contemporaneous with Shakespeare, but did not exist in the time of Lear (who is a semi-mythological king from before the Viking invasions), which in its turn suggests that historical correctness in not high on Shakespeare’s agenda. In fact, he is probably more interested in addressing current afairs in an indirect (and therefore comparatively safe) way than to say something about the ancient past. Furthermore, we might note that even though the speakers are earls, they do not speak in verse, as is the case with high-born characters in Renaissance tragedies. Instead, they speak in prose, which indicates that the tone and mood is informal and friendly (and that it should probably be performed as such by actors).

Next, let us look at what it says about the division of the kingdom. None of the king’s three daughters are mentioned. The two eldest daughters are hidden behind the names of their husbands, the Dukes of Albany and Cornwall and the youngest daughter – Cordelia – is not mentioned at all.

Next, let us look at what it says about the division of the kingdom. None of the king’s three daughters are mentioned. The two eldest daughters are hidden behind the names of their husbands, the Dukes of Albany and Cornwall and the youngest daughter – Cordelia – is not mentioned at all.

Despite the fact that Lear has three daughters, they talk as if the plan is to divide the kingdom in two parts rather than three, and it seems that one of the parts will be richer and larger than the others – hence the question about who Lear’s favourite may be. The irony is that the kingdom will in fact be divided into two parts rather than three, because the King has a falling-out with his youngest daughter, so she gets nothing. Shakespeare’s original audience will have been aware that this was about to happen, but Kent and Gloucester could have had no way of knowing. They simply leave Cordelia out of the conversation because she is unmarried.

Thus we see that what the characters could realistically know doesn’t really come to bear on what is revealed by what they are saying: when we study a moment of exposition, we should not be distracted by character psychology or what they may or may not know – instead we need to look at what the words they speak might reveal on a structural level: their implication that the kingdom will be divided into two parts is a foreshadowing of what will actually happen.

See this page for a more detailed discussion of fictional characters.

This first exchange also tells us a lot about what kind of society we are in. There is a king. We might assume that he is something of a control freak, as he seeks to determine the future shape of his kingdom before he has passed away, wanting to leaving nothing to historical happenstance. He is an all-powerful monarch, whose word is law (so far). And this is a patriarchal society, in which the daughter’s husbands – and not the daughters themselves – are the actual inheritors of the king’s lands and powers.

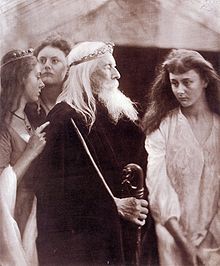

Edmund

It doesn’t take long, however, before the conversation shifts to what will become a major subplot in the story. Kent notices a young gentleman and asks if it is Gloucester’s son (there is no stage direction here; we have to imagine that Edmund appears somewhere else on the stage, cf. blocking in the key to theatrical vocabulary). Gloucester’s punning answer reveals a degree of shame in admitting that this is the case. In effect Gloucester states that Edmund is his mother’s son, and that said mother was unmarried. This means that Edmund is Gloucester’s son out of wedlock – what they used to call a bastard, but which may with more propriety be called an illegitimate child.

Gloucester adds that there is an older brother (we later learn that his name is Edgar), that he gladly calls his own, because he is legitimate. Later, Edgar will emerge as the play’s hero (of sorts), while Edmund, the bastard, becomes one of its chief villains. Is it possible, perhaps, that Edmund overhears his father’s evasive reply to Kent and becomes jealous of his brother, who is ‘by order of law’ a more loved child? It might be, even though Gloucester goes on to claim he loves both of them equally.

We also learn about Edmund, from Kent’s description of him, that he is probably handsome. But it is ironic, however, that Kent claims that the ‘issue’ (result, child) is ‘so proper’. Edmund, of course, is not proper at all, but someone who will cause a lot of pain and death in due time. Shakespeare was interested in how appearances might deceive, and it is probably significant that this theme is brought in so soon.

Conclusion

That is a whole lot of information baked into eighteen lines of conversation, and much more could have been said about word choices (for example: ‘moiety’ usually means ‘half’, supporting the notion that the kingdom will be split in two rather than three parts), jokes (Kent’s ‘conceived’ means to ‘understand’, but is also a pun on ‘to conceive a child,’ i.e., have sex) and much more. Would we be able to understand this much from the conversation on a first read-through or from listening to a performance? Probably not. In fact, as you have seen, a close reading of the type we have performed here relies on us knowing the rest of the play quite well, on knowing a thing or two about its historical context and having insight into the early modern English language as well as conventions of dramatic speech in the renaissance.

Looking back to the purposes of speech, we can confirm that this short dialogue functions as:

- Exposition of plot and character: we learn about the division of the kingdom and are introduced to a large number of important persons.

- Exposition of interiority: we find out about the somewhat fraught relationship between Gloucester and his two sons, and we understand that Gloucester is somewhat uneasy about having fathered a bastard.

Next, we will look at an example of a monologue.

What speeches do: Monologue