Poems often organise their lines into groups and set these groupings out on the page as separate units. More often than not, these units will be one of two things: a verse paragraph or a stanza.

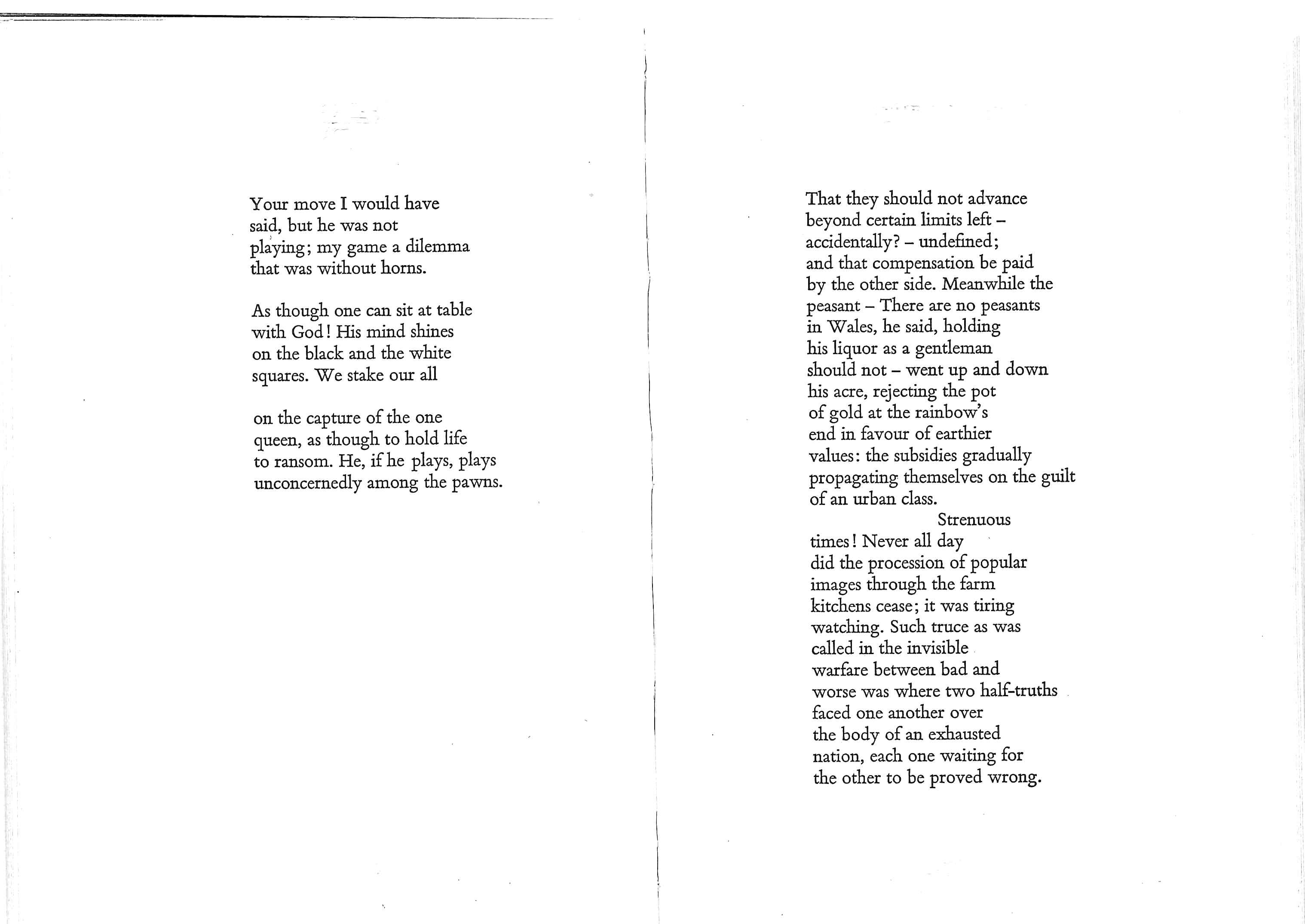

The difference between a verse paragraph and a stanza can easily be spotted by the way they are printed on the page. The poem on the left-hand side of the illustration below, for instance, consists of three stanzas and we know this because there is a whole line space – a complete stretch of blank page – between each set of lines and the next. The poem on the right, by contrast, consists of two paragraphs and we know this because about half way down, one of the lines does not hug the same left-hand margin as the rest, but it starts at the same point that the line above it ends.

Verse paragraphs and stanzas do not only look different on the page, they also serve different purposes and should accordingly be interpreted in different ways.

A verse paragraph serves the same function as a paragraph does in prose: determined entirely by content, it marks the point at which the poem moves either from one topic to another topic or from one aspect of a topic to another aspect of that topic.

A stanza, on the other hand, is first and foremost a formal device. It may well be the case (especially in older poetry) that each stanza constitutes a complete unit of sense in itself and that the movement from one stanza to another accordingly also involves a movement from one topic (or one aspect of that topic) to another. This, though, is not necessarily what determines either the size of each stanza or the point at which one stanza breaks off and another begins.

For this reason, we should treat the stanza in much the same way we have learnt to treat the line: as a formal device that conveys meaning in and of itself in a manner that may variously affirm, reflect, deepen, question or even actively work against whatever it is the individual words, phrases and sentences it contains might be thought to say.

Like the line, moreover, the stanza is distinctive to poetry (which is to say, you will never find stanzas in prose). As such, it is a crucial element in determining what poetry as poetry can say, do and, therefore, mean. In order to gain a preliminary sense of what stanzas do and thus of the contribution they make to a poem’s overall effect and meaning, we will first familiarise ourselves with the history of the word stanza and then with the history of the stanza in poetry.

The stanza as a standing place or room

The stanza gets its name from the Italian word for a standing place or room. This is useful to know because it offers a visually powerful and effective image for thinking about how individual stanzas work and how they contribute to the poem to which they belong.

Imagine, that is, that a poem is a house and that each of its stanzas is one of its rooms. In a real house, the number of rooms, the size and spaciousness of each room, the regularity (or otherwise) with which the rooms are structured and distributed throughout the building, and the manner in which these rooms connect with another, all affect the kind of life one can live there and what it feels like to live that life. By regulating the pace and rhythm through which we move through the house, and by influencing the thoughts, feelings and psychological states we pass through as we do so, the physical structure of the rooms accordingly contributes both individually and collectively to the structure of the life we experience as we carry out our various tasks and interact with the other people, animals and objects which also reside within those rooms and that house.

Much the same can be said of a poem divided into stanzas. If that poem consists of several short stanzas, each of which is self-contained in meaning and ends with a full stop, for instance, the experience of reading it could be likened to the experience of living in a home that consists of several small rooms, each with its own specific function and each with a door at either end that has to be opened and then closed as we move from one area and activity to the next.

A poem that consists of longer stanzas, on the other hand, might feel rather like living in an open-plan residence, much of which does away with doors and internal walls and is comprised instead of shared areas of activity that flow into one another and interact without the hindrance of any externally imposed barriers.

The manner in which the individual rooms of a poem contribute to the experience of moving through that poem, of encountering and interpreting its individual words and phrases, and thus of making sense of the whole will inevitably vary from poem to poem. Nonetheless, to think of its stanzas as rooms in a house will almost always prove a useful point of departure.

The stanza as a dance floor

Many historians of poetry have claimed that stanzas became an integral part of poetry at an early stage of its history because of poetry’s close association with music. Regardless of whether the words were written to fit the music or the music was composed to accompany the words, both needed to conform to the same pattern (or patterns). As with modern-day pop songs and their division into verses, choruses and sometimes one or more movements besides, each group of words had to fit one or other of the piece’s fixed set of repeating tunes. The stanza at this early stage of its history, then, emerged as a useful way of marking in print which group of words corresponded with which tune.

There are a number of general qualities stanzas acquire from this association with music which might be worth bearing in mind when evaluating the particular contribution they make to a given poem

- they can often enhance the musical and song-like quality of a poem (in contradistinction to verse paragraphs, for instance, which tend to emphasise the discursive, conversational or argumentative quality of a poem)

- they contribute an extra layer of patterning to the poem (which can then be assessed for such things as its regularity, variety and so on)

- they help instil a sense of movement and even sometimes dance in the poem (which is important for creating in the reader a sense that the poem is an activity in which one engages)

This last point is worth emphasising, because occasionally the characterisation of the stanza as a standing place or room has led readers misguidedly to think of the stanza as something static. Rather – and as I tried to emphasise in the analogy I drew earlier between moving through stanzas and moving through rooms – it is only a standing place in the sense that it provides the standing room within which a dance or any other kind of movement might take place.

With these configurations of the stanza as a standing place, a room, a song and a dance in mind, we will now proceed to outline some strategies for making sense of their presence in individual poems.